by Philip Marien

IFATCA Communications CoordinatorFollowing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, countries of the European Union have prohibited all Russian-owned, -registered, or -controlled aircraft, including private and charter flights, from landing in, taking off from, or transiting any EU nation. Switzerland, the UK, Canada, the US, and several additional countries have imposed similar bans. Reciprocal airspace closures by Russia’s Federal Air Transport Agency (Rosaviatsiya) have prompted flight schedule changes and lengthier flight times, as carriers are forced to adjust routes.

It is not the first time that airspace closures were used in political disputes: in June 2017, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Egypt severed diplomatic relations with Qatar and banned Qatar-registered planes and ships from utilising their airspace and sea routes, along with Saudi Arabia blocking Qatar’s only land crossing. The dispute was only resolved in 2021.

While these bans sound straightforward, things are a little bit more complicated.

Territory

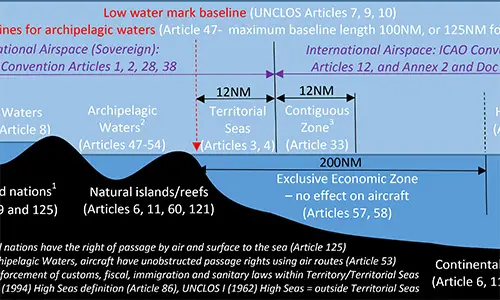

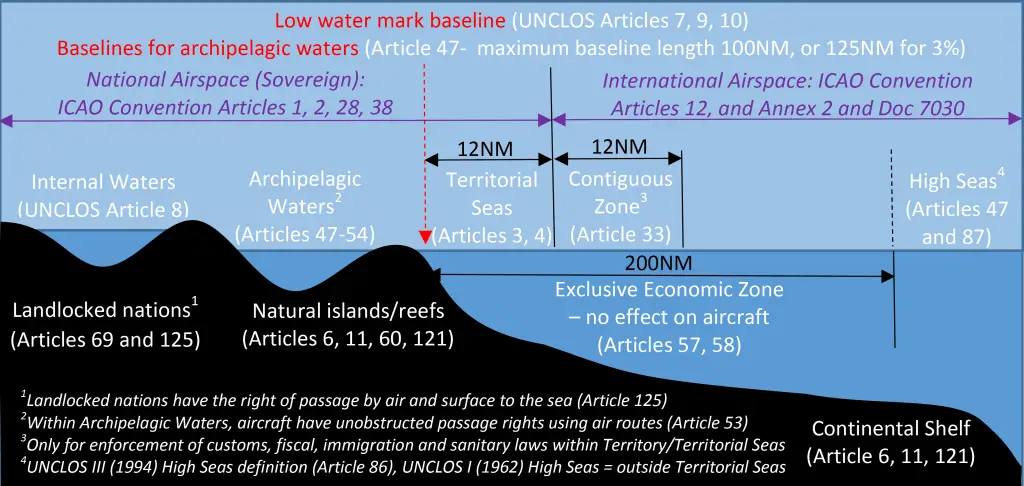

By international law, a state “has complete and exclusive sovereignty over the airspace above its territory”. The legal basis that defines what constitutes a territory is the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which, contrary to its title, also affects airspace and the operation of aircraft. UNCLOS aligns a country’s sovereign airspace with the maritime definition of territorial waters as being 12 nautical miles (22.2 km) out from a nation’s coastline.

The coastline consists of ‘baselines’ in UNCLOS, which are generally based on the maritime shoreline, whether the shore is continental in nature or the outermost part of a chain of islands, i.e. an archipelago. To be considered as such, the islands must be no more than 100NM apart, except for 3% of the islands, which may be 125NM apart. The sovereignty of archipelagic airspace is not the same as other territorial airspace, as aircraft have the right of ‘continuous and expeditious’ passage. It means that unlike territorial airspace, aircraft cannot be denied transit through such areas.

Airspace that is not within any country’s territorial limit is considered international, analogous to the “high seas” in maritime law. It is worth noting that the terms ‘national airspace’ and ‘international airspace’ are descriptive in nature, but do not appear in UNCLOS (or in ICAO’s Chicago Convention for that matter).

Outside their sovereign airspace, States do not have the jurisdiction to issue rules for foreign aircraft operating in that airspace. They may enact laws/requirements for their own citizens and aircraft registered in their own State for operations within international airspace, but they cannot do this for all aircraft.

(white/red = UNCLOS; purple = Chicago Convention)

source: ICAO ATM/SG

Air Traffic Services

Outside their sovereign airspace, a country may assume responsibility for providing air traffic control services in parts of international airspace through international agreement. An airspace for which a country is responsible under the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) is called a Flight Information Region (FIR). For a coastal state, the FIR consists of the airspace above its land and sea territory plus any international airspace in respect of which ICAO has assigned responsibility to that state. For instance, the United States provides air traffic control services over a large part of the Pacific Ocean, even though the airspace is international.

Civil aircraft wanting to operate in such an FIR must comply with the Chicago Convention and its Annexes. It means that they cannot operate in a particular flight information region without adhering to ICAO rules: filing a flight plan, obtaining a clearance and adhering to ATC instructions.

While an airspace can be closed for all aircraft – e.g. for flight safety reasons, as was done for the airspace above Ukraine and Moldova at the start of the Russian invasion – the ICAO Convention does not allow a state to deny access to international airspace for specific flights based on the country of registration.

For territorial airspace, the issue a little bit less clear. The ICAO Convention should guarantee the freedom to overfly as long as the rules and regulations of that country are adhered to of course. Pierluigi Di Palma, chair of Italy’s ANSP ENAC remarked: “…We see international treaties being violated to some extent with respect to the airspace ban decided by the West against Russia.” According to Di Palma, the airspace ban decided by the European Union bends both bilateral treaties and the ICAO rules. An anonymous spokesperson for the EU refuted this and said that the ban was fully compliant with international law.

State Aircraft

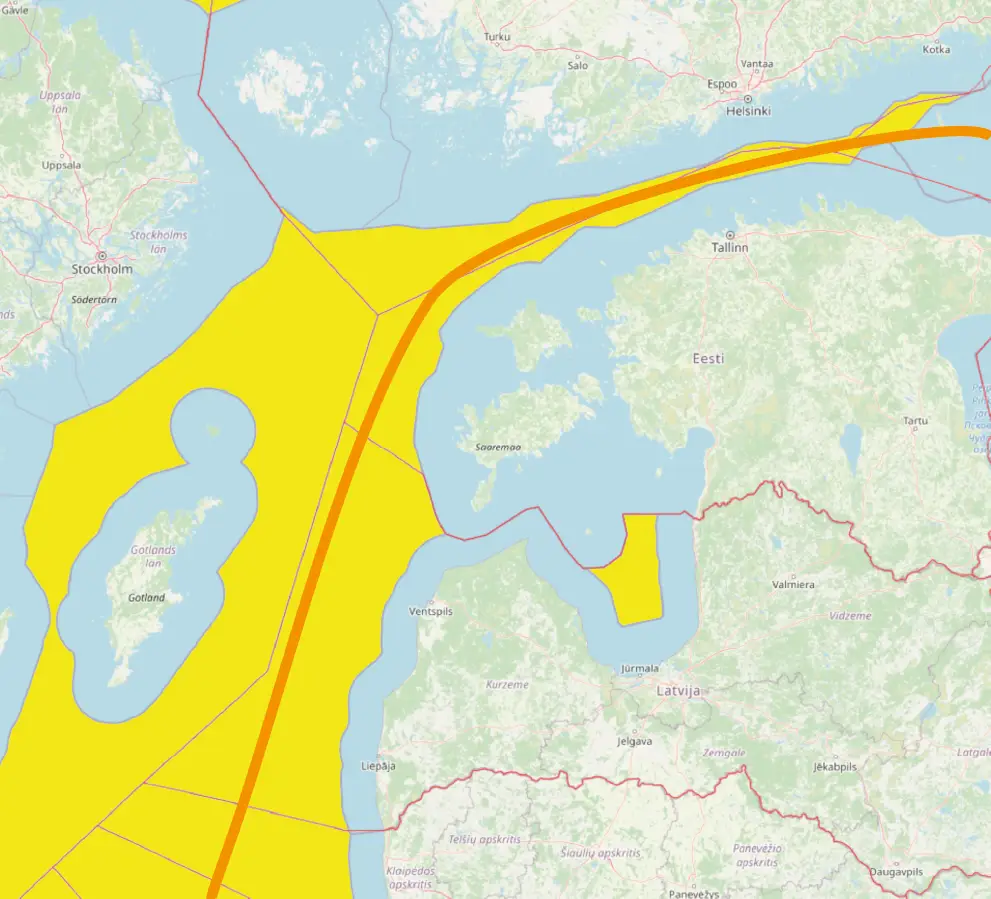

As the convention and its annexes are not applicable to State aircraft, a state aircraft operating on a flight plan in international airspace is complying with civil requirements voluntarily and strictly speaking does not require an ATC clearance to enter the airspace, even if this is controlled. The convention places some requirements on States regarding the interaction between military and civil aircraft, like requiring regulations to have ‘due regard’ for the safety of navigation of civil aircraft (article 3); and to ensure that military aircraft do not endanger civil aircraft when using weapons or when intercepting (article 3bis). Using international airspace, aircraft can continue operating in and out of the Kaliningrad enclave, which is surrounded by EU countries that have banned Russian aircraft.

NOTAM A1941/22

MILITARY INVASION OF UKRAINE BY RUSSIAN FEDERATION - ALL RUSSIAN

REGISTERED AIRCRAFT AND AIRCRAFT OWNED, CHARTERED OR OPERATED BY

NATURAL OR LEGAL PERSONS FROM THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION OR BY OPERATORS HOLDING AIR OPERATOR CERTIFICATE (AOC) ISSUED BY THE RUSSIAN

FEDERATION AUTHORITIES ARE PROHIBITED TO ENTER, EXIT OR OVERFLY THE NETHERLANDS AIRSPACE EXCEPT HUMANITARIAN, SAR AND LEASED AIRCRAFT ONE-WAY RETURN FLIGHTS WITH THE PERMISSION OF THE APPROPRIATE DUTCH AUTHORITIES AND IN CASE OF EMERGENCY LANDING OR EMERGENCY OVERFLIGHT. These flights use a corridor of international airspace over the Gulf of Finland, skirting in and out of the Helsinki and Talinn FIR. The civil flights are controlled by Estonian ATC, while the state flights mostly use the ‘due regard’ principle. Interestingly, the civil flights owe route charges that are normally collected through EUROCONTROL’s Central Route Charges Office. And the majority of these flights is performed using aircraft that were leased from international lessors, but that have been re-registered in Russia in a retaliation for the international sanctions. Despite the obvious illegality of using such aircraft, there seems to be little or nothing international law can do to stop these.

While there seems little doubt that the measures taken against Russia are justified, there is a clear risk that such measures now become the norm in other conflicts. Countries may take similar measures to try and settle territorial, economic or other conflicts. The Convention on International Civil Aviation was established to promote cooperation and “create and preserve friendship and understanding among the nations and peoples of the world.” Nearly eighty years since it was drafted, it seems that concepts like “freedom of the air” will be facing tough challenges in the future.