by Philippe Domogala

IFATCA Contributing EditorOn December 7th, 1944, exactly three years after the attack on Pearl Harbor and six months and one day after the Normandy invasion, with the war still raging in Europe and the Pacific, delegates from 52 countries signed a new Convention on International Civil Aviation, the Chicago Convention. We still use the annexes of this convention today.

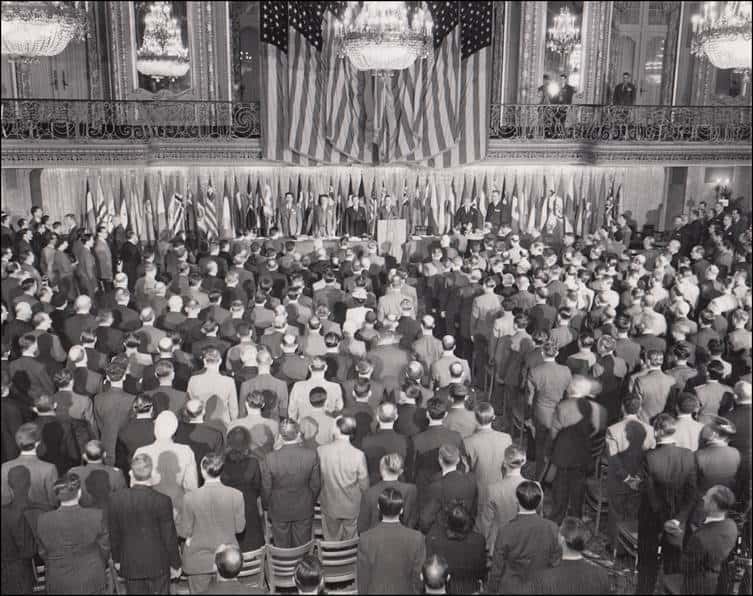

U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt had invited 55 Governments. The conference opened on November 7, 1944, with 700 delegates from 52 countries sitting in the ornate ballroom of The Stevens Hotel in Chicago. They would be there for over a month!

At the end of 1944, many assumed the war would end soon with an Allied victory. International air commerce, severely compromised since 1940, would become an essential contributor to a post-war economic recovery. International routes no longer existed at this time, and nearly all European airlines were grounded or operating minimally. US airlines, mainly Pan Am, still operated and even prospered during that time.

After the First World War, in 1919, a conference was held in Paris, and the first international aviation convention was adopted, designed to open Europe to air traffic. However, under the arrangements then made, years of discussion were needed before the routes could be flown. In 1944, the participants were determined not to repeat that same mistake.

Adolf Berle was the US Deputy Secretary of State for Transport and the head of the US delegation. President Roosevelt had also designated Berle as the conference’s chairman. But in 1943, Berle had “that Americans could go anywhere and sell anything; but that other countries must be excluded not only from the American market but from any market in which the United States can gain dominance”. This statement had stirred up serious concerns in other countries at the time.

In addition, Pan Am had long been America’s “chosen airline and instrument” on international routes, and its CEO, Juan Trippe, was openly in favour of a continued U.S. (i.e. Pan Am) domination of the global skies. IN 1942, Trippe said it was essential “that we should seek landing rights without offering them,[ …] find plausible reasons to deny most requests for landing rights to others countries and keep our concessions to a minimum.”

This was not a good setting to invite other States to cooperate. Many countries, especially the United Kingdom, worried that the United States, which had developed a vast capacity to build transport aircraft during the war, would quickly dominate the world’s air routes. As early as 1941, an internal UK government report on the future of international aviation had said: “The choice before the world lies between Americanization and internationalization“. They said the U.S. needed to promote “a generalized settlement of the problems of air navigation rights on an equitable basis.” The UK’s view was representative of that of most participants.

Canada understood the gap that separated the USA’s and the UK’s views on post-war aviation. While a loyal Commonwealth country, Canada was also wary of putting too much ideological distance between itself and the USA. Thus, it found itself in the role of mediator between the UK and the USA. This is one of the main reasons why, at the end of the conference, Canada’s offer for Montreal as the seat of the newly formed Organization was chosen over New York.

Canada produced a draft international air convention in March 1944. Their proposal was the subject of widespread discussion and broad agreement. Canada proposed the establishment of an international air authority and that all nations should grant the “four freedoms” described in the draft treaty to all airlines “whose operations have been authorized by the authority.”

However, during the conference little progress was made in conciliating the USA and UK positions: the USA wanted “freedom in the air”, while the UK advocated for “order in the air”.

The first order of business in Chicago was for Berle to deliver a statement of the USA’s position. The USA, he said, hoped the conference would address itself to three major items: routes, rules of the air, and institutional arrangements. But there were still significant differences of opinion between the UK and the USA: The most pressing was related to traffic permitted on so-called “fifth freedom” flights, i.e. an operator’s ability to fly to another country, pick up goods or people, and carry them to a third country. This is still an issue in 2024!

Four committees and an extensive array of subcommittees were created. All worked hard with some success on technical issues and failures on regulations and market access. However, by the time of the third plenary meeting on December 5, they had quietly produced nothing less than the essential foundation for the future of international aviation. The most important product of their work, of course, was the Chicago Convention itself. It was, and still is, the foundation of global civil aviation.

Committee II, which covered technical standards and procedures, had established ten subcommittees that, in a few short weeks, somehow produced the drafts of the Annexes we still use today. They covered communications, airworthiness, air traffic control, licensing, and other essential requirements. An interim agreement established a Provisional International Civil Aviation Organization (PICAO) while the participating countries ratified the Convention. On March 5th 1947, it received the requisite 26th ratification. The Convention went into effect on April 4, 1947, and PICAO became ICAO that same day.

A nice anecdote illustrates the international cooperation at the time: on the day before the conference closed, delegates conducted an election of the 21-member Interim Council of the PICAO that produced an unexpected crisis. India, despite its 400 million population and strategic location, had not won a seat. The omission meant that the UK might have to withdraw its support for the agreements achieved at the conference, thereby calling into question the support of all other Commonwealth members. Understanding the magnitude of the problem, the chief delegate of Norway immediately asked for unanimous consent to permit India to replace Norway on the Council. The conference was still reeling from the magnanimity of Norway’s gesture when the chief delegate of Cuba asked for the floor. He said he had learned of Norway’s intentions only 10 minutes earlier and had not had time to consult his government, but he nevertheless offered Cuba’s seat to India and asked that Norway’s membership be restored. The Cuban offer was accepted. The work of the Chicago Conference was thus saved by what may have been one of the most consummate demonstrations of gallantry in the annals of multilateral diplomacy. Berle concluded the proceedings with justifiable pride. “History,” he said, “will approach the work of the conference with respect. It has achieved a notable victory for civilization. It has put an end to the era of anarchy in the air.” The work done in Chicago, he said, had established “a foundation for freedom under law in air transport”.

Interestingly, US President Roosevelt and the UK’s Prime Minister Churchill considered the Chicago Convention a failure, as it did not agree on market shares and routes. Churchill also expressed his views of internationalization, “If by this “internationalization of air transport” is meant a kind of Volapuk Esperanto cosmopolitan organization managed and staffed by committees of all peoples great and small with pilots of every country from Peru to China (especially China), flying every kind of machine in every direction, many people will feel that this is at present an unattainable ideal.” But both were wrong.

The introduction to the printed proceedings of the Chicago conference, published four years later, rightly stated: “It can safely be said that the International Civil Aviation Conference at Chicago was one of the most successful, productive, and influential international conferences ever held.”

The above text is based on an article from The Air & Space Lawyer, Volume 32, Number 4, 2019, "The making of the Chicago Convention", by Jeffrey N. Shane

The International Civil Aviation Organisation, ICAO, celebrated this milestone on December 4, 2024, at the Chicago Hilton Hotel, formerly The Stevens Hotel, where the Convention was adopted. An EASPG meeting, where nearly all European, North Atlantic States and International Organizations within aviation were represented, also commemorated the occasion at the ICAO regional office in Paris on the same date. For IFATCA, Philippe Domogala attended and, as the oldest delegate – his first ICAO meeting representing IFATCA as RVP Europe West was in 1986 – he was asked to make a speech. He used this opportunity to reaffirm the excellent cooperation IFATCA has with ICAO, who, despite our observer status, has always treated us with respect and attention: “As the oldest delegate here let me, on your behalf, congratulate ICAO on this anniversary. Oldest delegate, because my first meeting here in this building dates back to1986. It was an ECAC meeting, as in those days they were quite powerful: in 1986, ECAC had 30 states while Eurocontrol only had 8!

We were the first ATFM group setting the basis for the central flow management organization which will later become the CFMU and now the Network Manager. A success. But I also spend numerous meetings here developing MLS which was supposed to replace ILS by 2010. The famous AWOG meetings. That did not work as planned!

Those who know me, know that I am a history fanatic. So, let’s look back to 1944, 80 years ago. Mankind was in the middle of a global war. It was six months after D-Day invasion in Normandy and only three years after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Let me go quote Adolf Burley, the US secretary of transport and chief delegate of the US delegation during the 1944 convention that we celebrate today. Yes, another Adolf but not the one we all know. He said: “History will approach our work at this conference with respect. It will be a victory for civilization and put an end to anarchy in the air. It will be the foundation for freedom and the law in air transport.” What a visionary!

ICAO actively encourages good cooperation between States. In 1944, fifty-two countries met and decided to go forward. To continue the work, they created a council of 21 States. However, during the vote, India with 400 million people did not have a seat and the UK complained. Norway gracefully withdrew its seat and offered it to India. This prompted Cuba to ask that Norway’s seat be restored and offered its own seed to India! That cooperation spirit between states in ICAO is still there today.

On behalf of all, and especially IFALPA and IFATCA, I would like not only to congratulate ICAO for the 80th anniversary of their convention, but I also want to take this opportunity to thank the European regional office and his dedicated staff for the continuous support they give to States in solving the problems we have all encountered over those years. ICAO does not only support the States but also international organisations such as IFALPA and IFATCA. They have done this since the beginning – 1948 for IFALPA and 1961 for IFATCA – and despite our observer status we have always been regarded in the same manner as the States.

Eighty years is in achievement, and we are happy to participate in this celebration. We thank you publicly for the work you do to promote safety. We wish you all the best for this 80th anniversary and looking forward to the 100th one.“

Philippe Domogala

December 4th 2024